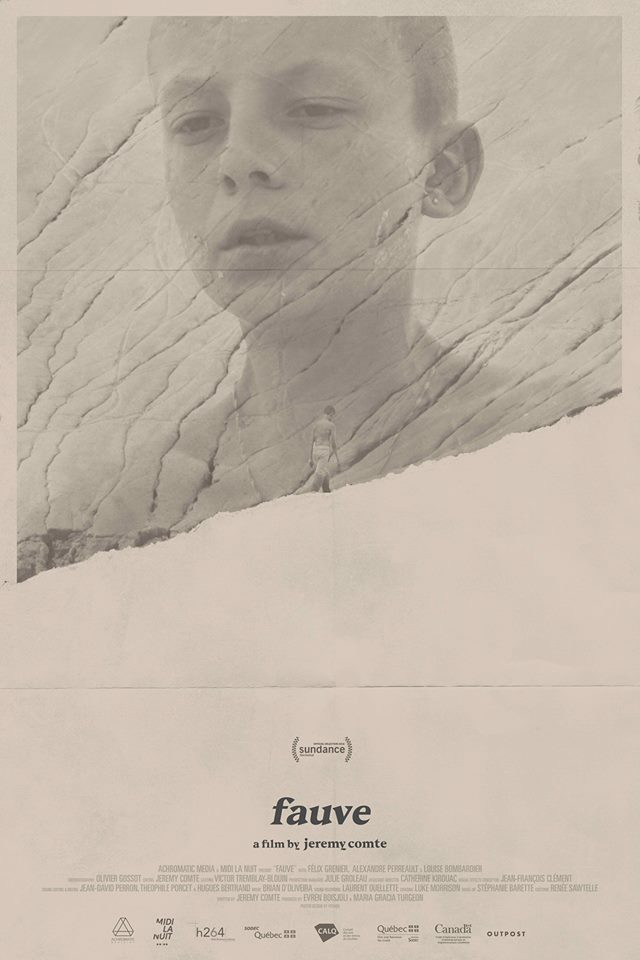

Directed by Jeremy Comte –

At an isolated surface mine in the Quebec countryside, two boisterous young boys run wild, challenging each other to reckless tests of endurance and daring, with only Mother Nature as their witness.

GFM: Congratulations on this very minimalist and surreal film!

Jeremy: Thank you so much.

GFM: Could you tell us a little bit about your background and your work in film?

Jeremy: I wanted to be a filmmaker since I was twelve years old. I started making skateboard films when I was a boy because I was very passionate about skateboarding. Then I studied film production at Concordia University in Montreal and moved into documentaries, music videos and commercials and began writing my first short films, and now I’m on to my first feature. I made my first real documentary when I was seventeen, where I mixed action sports, focussing on long boarding and went to the Banff Modern Film Festival and then toured the world with it. So that was my big milestone at seventeen.

GFM: Please tell us about your previous short documentary Paths.

Jeremy: Yeah, that’s a documentary about exploring humanity. I traveled the world for five months and I wanted to show that even if we’re all different culturally, we’re all humans. Some of the encounters I had with people were planned and others were more random, but as I went along I tried to make connections through all those portraits I was capturing.

GFM: Let’s talk about your Oscar nominated Fauve. Where did this story come from?

Jeremy: It comes from childhood nightmares I had when I was a boy of sinking in quicksand. I think this subject was very popular at the time in film and TV, like Never Ending Stories, for example, so it kind of stuck with me. Also, growing up in the countryside I used to take long walks with my friends in the woods and we would pull pranks on one another. There was this rivalry between my best friend and me and about four years ago it all came back to me and I decided I wanted to make something that explores childhood in a very real way – like what if one of those pranks could have turned very bad and gone too far? I wanted to explore this while bringing the theme of Man vs. Nature forward.

Growing up surrounded by nature was immersive and I feel like children sometimes manifest more primitive traits – sometimes we forget that we’re actually animals in some ways. There is something so impulsive in us and I feel with children it might manifest itself even more. So I was very interested in those themes.

GFM: The location is magnificent. How did you discover it and what was it like working there, especially with your cinematographer Olivier Gossot?

Jeremy: Well, I knew that the quicksand scene would take place in a quarry because that is where I always imagined myself in my dreams as a kid. I was always fascinated by what they were like inside. I knew of a place in Montreal with a lot of quarries where I began scouting with my producers. The last one that we found was the place that we shot at and it was so different from the other ones. It looks like a moon landscape. I really wanted the film to feel atemporal and like we don’t know exactly where it is. In my original script the kids were playing with old abandoned cars, because you know, that’s what I used to do when I was a kid. But then beside that surface mine, we magically found those abandoned trains.

In terms of working there with my cinematographer, I really wanted the film to be, like you said, very minimalistic, and to keep it very raw and for the events to be immersed in the landscape. It was important to me that the first part of the film would be very lively and shot with a handheld camera, but then as soon as the kids get stuck in quicksand the camera looks down and becomes more like crane movements and long tripod shots, so it is more claustrophobic. I wanted that transition through camera and movements.

GFM: Was the quicksand real or was it sort of just muddy?

Jeremy: The quicksand was an illusion! The problem was that we found the location the summer before and it was very dry, so we knew we could make it muddy, but when we came back a year later the whole valley was filled with water, so we had to pump the water out. But the quicksand is maybe one foot of mud and gray solid ground. We had to dig a hole and fortify it with wood and we filled it with oatmeal. Oatmeal has the consistency of dirt, but it is more comfortable for the actor. We had to keep temperature checks because it gets really cold inside the hole. So that was a real danger.

GFM: What was your experience like of working with your young lead actors Félix Grenier (Tyler) and Alexandre Perreault (Benjamin)?

Jeremy: We wanted to work with young actors so we reached out to schools around the area where we were shooting, and we auditioned seventy kids, but Felix and Alexandre both stood out by their transparency and confidence. They were just so energetic and open. We did a lot of rehearsals with them on location and I didn’t give them a script. I just gave them lines to memorize by heart and they were also very collaborative, so sometimes they would make suggestions for lines. It was a very fun process.

GFM: Felix’s emotional breakdown towards the end is heartbreaking. How did you help prepare him for this moment?

Jeremy: The last scene was a lot of work and it was my worry from the start because it is a big emotional scene and I was wondering if Felix would be able to get there. Felix came to Montreal beforehand and we rehearsed with extras to play the mom. When it came to doing it on set, it was the last scene we were shooting, so we really kept it to the end. Then in the car I was preparing him because he needed to be hyperventilating and very emotional, so when he came to that take we discussed more personal things. We talked to him just like a friend. We explained what the character was going through, but we were also trying to make him relate to something that maybe he could have experienced himself. He really, really understood. He is so brilliant.

GFM: And your actress Louise Bombardier is an amazing counterpart in that scene, as you can exactly imagine a woman showing that kind of empathy to a lost young boy.

Jeremy: Yeah, totally. I mean, for myself, that woman was so important because when I used to do that with my friends we would sometimes wander very far out. I remember a woman picking me up like that, so this character is maybe the mother that he doesn’t have, you know? She makes him feel so understood about whatever has happened, so it makes him open up and cracks his facade. The female character is so crucial to the story.

GFM: Audiences will likely be trying to make connections between the film’s title and the Fauvism movement. Could you discuss that?

Jeremy: Yeah, of course. Well, Fauvism was a big inspiration for the title. The movement is known for paintings with those super vivid landscapes, and the last shot of the film is this vivid landscape of nature. Fauve in French also means ‘wild beasts’ and refers to a burnt orange colour, so it made so much sense to have this title because it has so many dimensions to it.

GFM: What is important about the short film format for you?

Jeremy: It’s an art in itself for me, and a different way to express oneself in such a short amount of time. You cannot develop a character too much. So, it’s about telling a story in a very contained way that can send a strong message. It’s about working simply and with not too many characters or locations and working around that.

GFM: Please describe the moment that you found out you’d been nominated for an Oscar.

Jeremy: I was with my whole team at my distributor’s office, which is in the same building as the other Canadian film Marguerite that was nominated for an Oscar in the same category. We were both in our own room, but side-by-side, and we leaned out – we had weak connection so the feed was a bit delayed. We heard them scream first, and I was not sure if it was a good or bad thing because maybe they got it and we didn’t. But then my phone started vibrating a lot, and then we saw the nomination and we knew that our dream had come true. There was screaming and jumping, and it was a wonderful moment!

director Jeremy Comte