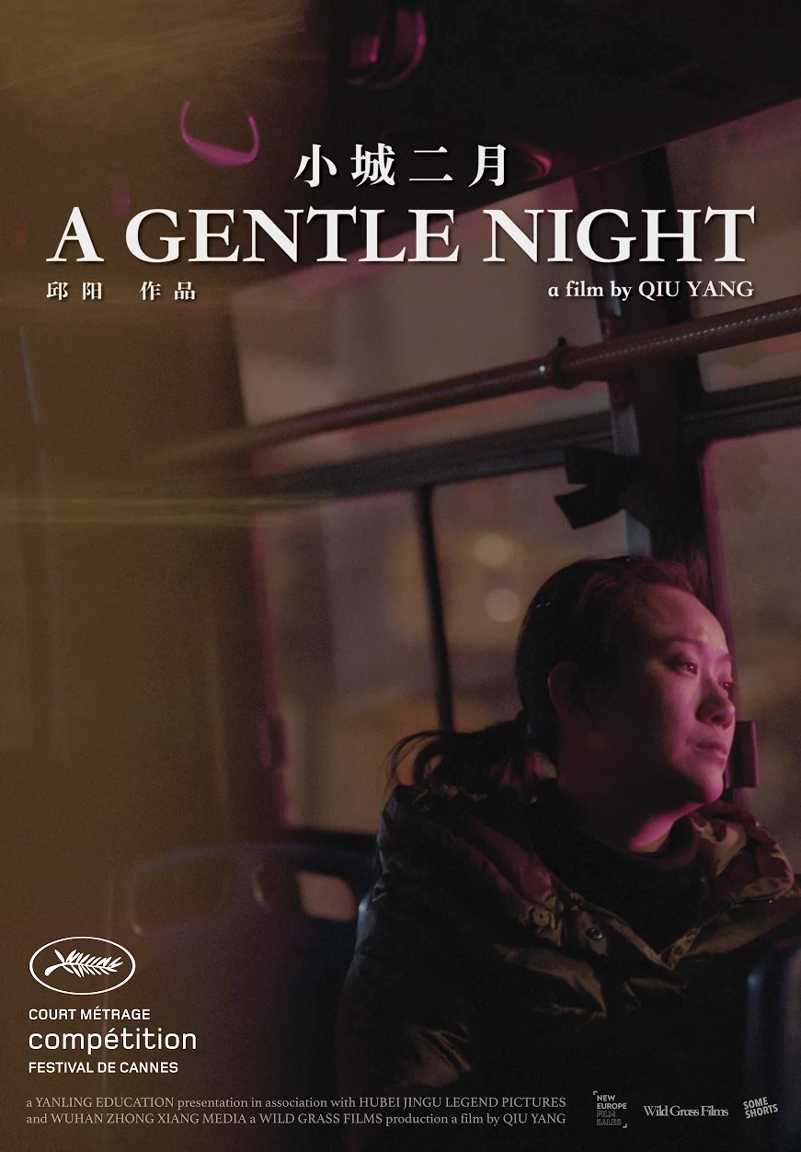

Directed by QIU Yang –

In a nameless Chinese city, a mother with her daughter missing, refuses to go gentle into this good night.

GFM: Your graduate film Under the Sun competed in the prestigious Cinefondation selection in Cannes 2015. How does it feel to be returning to Cannes with A Gentle Night to compete for the Palme d’Or?

Qiu Yang: It’s very surprising and lucky because I never aimed to have it in the competition. Since it’s been two years, I just wanted to do one more film to add on. I made the film earlier this year and didn’t think about it at all. I didn’t prepare anything, so I feel fortunate and honoured.

GFM: Both films deal with characters facing tragic circumstances, which are very personal. Where do you find inspiration for your stories?Qiu Yang: Most of the inspiration for my stories comes from real life. I was born and raised in China, and still live there, and it’s a place where you will be able to find drama and stories everywhere in daily life if you look closely enough. Many of the stories in my films happened in my family or are real stories that I heard about from friends or newspapers.

GFM: Your films are beautifully shot and framed in a way that makes viewers feel like they are a part of the scene, often by putting the camera behind the main characters as they are talking. Can you talk about how you make your decisions with your cinematographer for the visual style of your films?

Qiu Yang: The main thing that my DOP and I need to agree on before shooting is the style and feel, or tone of the film. Since it’s about social realism, we want something that’s very naturalistic, but also visually pleasing. For instance, we choose to use minimal lights and in Under the Sun we didn’t use lights at all. For A Gentle Night, we used two LED lights for the whole shoot and did a lot of location scouting in pre-production to try and find the perfect location, which already had a great lighting situation. It’s one of my requirements for the mise-en-scene, and all the DOP needs to do is enhance it a little bit. We also try to make decisions about the framing and how to shoot the film in pre-production. Basically, the whole film is shoot to edit, and it takes about four days for the editing process. I don’t do traditional coverage. Most of the film’s visual aspects are actually decided on in pre-production between my DOP and me. So, that’s basically how I work.

GFM: Another very interesting element of your films is the sound production, for example, the opening scene in A Gentle Night with the police sirens and cell phone ringing, as well as the crescendo at the end of the film with the sound of fireworks exploding. Can you talk a little bit about how that all comes together?

Qiu Yang: I always believe sound is at least 50% of the film. I actually think sound is more powerful than visuals. When you see something, you don’t necessarily believe it, but when you hear it, you believe it. That’s something that I think enables the filmmaker to expand the film beyond the frame because traditionally when you see a film, you see what’s in the frame, but when you do sound, you’re working with a lot of stuff that’s off-screen. That’s what I discussed with my sound designer, as I don’t want to just design whatever is inside the frame, I want to design the whole work and environment. I also think that sometimes I put details of the story into the sound design as a way to force the audience to pay more attention to the film. I think it creates a more engaging viewing experience.

GFM: You studied film in Australia at the Victorian College of Arts in Melbourne. Were there any challenges in going back to China to make your film?

Qiu Yang: Yeah, that’s for sure, because it’s an entirely different world. As everyone knows, there is still a lot of censorship in China, and policies and laws regarding the filmmaking industry are still not fully established. So, it’s very different. I try to apply all the best aspects of western filmmaking where possible, for example, only shooting for 10 – 12 hours a day. In China there is no policy and you can shoot for however long you want. When it comes to things that require permission, we kind of have to do it under the radar because it’s super complicated otherwise. I was able to get away with a lot more because I shot in my home town, Changzhou. I had more context and resources and didn’t need to apply for permission or shoot under the radar. Also, in Australia everyone has to sign contracts and it means something. In China, even if you sign an agreement to do something it doesn’t mean anything. People don’t care about it.

There’s a lot that you have to do in China when it involves people. You have to be friends with people to be able to shoot in their home or ask them to act in your film, and you always have to keep an eye on the authorities. People called the police on us twice during the shoot. It was really funny. Each time the cops arrived, they asked what the hell we were doing? However, we were lucky because one of the film producer’s parents works in the police department, so she was able to handle the situation for us and we were kind of protected. You need to be very street-wise to shoot in China. So, it’s very, very different.

GFM: What excites you most about returning to Cannes two years later?

Qiu Yang: I’m looking forward to saying hi to people at the festival and to be taking along a new feature script, which I’m writing at the moment as part of my Cinefondation residency program in Paris. I’m really excited to bring this project to Cannes to seek potential collaborators. I really want to try to make this – it’s the main, main thing now. I’ve been preparing the feature project for the past two years and having this short film selected for Cannes could be a really big help for the project.

director QIU Yang