Directed by Zamo Mkhwanazi

A pregnant prostitute, a taxi driver and an iPhone come together on an ordinary Johannesburg afternoon to decide the value of a life. Can two people, who do not know how to love, create a home?

GFM:

Having worked on over twenty-five television shows including The Lab, 90 Plein Street, Isidingo and Jacob’s Cross, your background in TV is extensive. Please tell us about your transition to short film.

Zamo:

The biggest reason I wanted to do film is that in television it’s far more difficult to have a creative vision of your own. In fact, a series is more the property of the broadcaster than the production company, and even the director has far less autonomy and say-so in how things are executed. In order to be able to exercise my creative vision, I knew that I needed to branch out from television.

GFM:

The Call captures an essence of Johannesburg incredibly well. This is the hustle and bustle of public transport seen from the perspective of Sibongiseni’s, who is a taxi driver. How does location play a role in the film?

Zamo:

All over the city in South Africa we have taxi drivers, which is a very interesting fact in our lives because it’s the only industry in South Africa that is 99% black owned. It comes out of a spirit of true entrepreneurship, so I have enormous respect for the industry. As we all know, however, it comes with enormous problems.

What really inspired the story, and particularly in terms of Joburg, is that I witnessed an encounter between a friend of mine and a taxi driver. The taxi driver had done something incredibly reckless on the road, and if it weren’t for my friend’s expert driving, all of us, including the taxi driver and his twenty passengers, would probably have been dead. In the heat of the moment when adrenaline was rushing through him, my friend went to confront the driver; as a South African you know you don’t confront taxi drivers. What struck me was the driver’s response, which essentially was no response at all. He remained deadpan just watching his passengers getting off and on, paying no attention to my friend’s tirade.

GFM:

Do you feel it was almost like business as usual?

Zamo:

Well you know that was the whole point – something switched in my mind at that moment. I realised that this man is a human being and he values his life no less than anyone else. I began to ask myself the question as to what had dehumanised him to the point where he was impervious to insult and the idea of killing himself and all these people; he’d cut himself off mentally and emotionally. I started to think about living in a city like Joburg, having to do that kind of job 16 hours every day, and how much a person could hate it. It’s not a game – every single moment that you’re on that road you could die. The taxi drivers also drive so badly that we feel free to throw abuse at them, and to hate them, without thinking about their side. I thought, “What does it feel like to live in a world where people feel that it’s okay to hate you?”

In addition to the long hours, can you imagine the enormous amount of strain knowing that at all times you are responsible for the lives of twenty random strangers? Is that really a fair existence, especially when you think about how little they earn, as well as the socio-economic issues around that? So in terms of Joburg, the city is the environment in which they operate, and that environment is not built to accommodate them.

GFM:

The incident in the film where someone smashes a brick at Sibongiseni’s window wouldn’t surprise South Africans. What do you think international audiences would make of it?

Zamo:

When you watch Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, for example, there are numerous references to things that are so uniquely New York, and he doesn’t bother to explain them to us. I realised that that’s what authenticity is about, and that if you understand it, you understand it – if you don’t, you don’t. If you’re having an authentically Joburg experience, and you’re a foreigner, you won’t understand – and that’s okay.

There is also the woman who flips him the finger, so it was kind of a way of saying that the antagonism doesn’t just come from the people who are outside the taxi, it also comes from the very people he transports. In many ways it’s justified because he drives like he’s carrying cattle – he doesn’t give a toss. I hope that an international audience is going to go “hah! that guy is pissed off because of the way he was driving”, but if they don’t get it, I’m also pretty okay with that.

GFM:

The film seems to deal with issues surrounding masculinity and conflicted male identity. Was Sibongiseni’s lack of dialogue a way to represent this?

Zamo:

Well, you know, his not speaking is, in fact, a huge part of what the story is about. Because, yes, as you say, it’s about tropes of masculinity, which affect men all over the world, but as a South African, I’ve observed how it affects South African men, which is the ‘strong silent type’ nonsense, and how difficult it must be. That lack of communication allows him to give as little as possible, but it also becomes his trap, where he’s unable to express his own wants and needs.

So, while his silence serves him, and protects him – because that’s really what it’s about – it makes him impervious to everything that’s going on and all the hate and anger that’s directed at him. If he’s silent, he’s not reacting to it, so he maintains a certain level of control. So the silence is not incidental, it’s not a gimmick.

GFM:

The phone calls and the phone itself play an important role in the film, almost acting as a symbolic call to his conscience. Can you talk about the calls as a narrative device?

Zamo:

In a blunt way, the phone is a tool of communication, and this is a man who doesn’t communicate. So just as an object, it represents the biggest challenge in his life, which is communication. The phone belongs to a nurse, who spends her time saving lives. He spends his time endangering lives. She falls asleep in his taxi, however, which is immediately a gesture of trust. When she calls the phone in an attempt to retrieve it, she is calling from home, which is why it constantly says “home” on the screen. This is significant, as Sibongiseni and his girlfriend are discussing the possibility of creating a home together because she is pregnant. That’s what having a child together does – it immediately makes that person your family.

So that phone becomes, yes, the call of his conscience, and also of his most hidden desires, which he constantly ignores and cannot communicate. His girlfriend engages with the phone. She picks it up and plays with the apps – she plays with the idea of home, whereas he doesn’t even allow himself to dream, to wish that for himself.

GFM:

Sibongiseni is played by well-known South African actor, Fana Mokoena. How did you get the script to him and what was the process of getting him on board?

Zamo:

[Laughs] Fana, was in fact not my first choice because he’s famous. I wanted a guy whose face you’d forget. I wanted this guy to be wallpaper. I wanted him to almost not exist. To me he’s the invisible man, you know, that’s what the taxi driver is. We live in a society that dehumanises them in many ways so that we often don’t think of them as people. Fana, however, is so recognisable. But let me tell you, it was not easy to get Fana Mokoena – Fana Mokoena is incredibly busy. He was doing five million things at the time and I wanted him to do this little script, which was eight pages, and he has no lines [laughs]. But when Fana was willing to meet with me, that was one of those moments where I went, ‘right, okay, so I’ve got something here’.

When I met him he interrogated me a lot – he made me feel pretty nervous, because it was a bit of a courtship, you know. But eventually I kind of convinced him. I said to him “tell me straight to my face if you don’t want to do this film so I can move on, because I can’t until I know that” and then he said, “what do you mean, of course I want to do this!” We went out drinking and chatting and really getting to know each other, becoming friends and at ease with one another, so by the time we got on set, I think things went a lot smoother.

GFM:

Congratulations on being selected to the South African Cannes Film Factory! What does this mean for you?

Zamo:

Thanks! It’s been an amazing experience so far. It’s been like, “right, you’ve been given the keys to a small part of this great kingdom, and do with it as you will, and it’s on your head.” There’s nobody holding your hand, there’s nobody forbidding you from doing anything, there’s nobody dictating to you what you can and can’t do. That’s a little bit scary, especially for someone who comes from television, where everything has parameters, especially with the budgets we’re used to here in South Africa. The challenge for me is to say, “no, there aren’t any limitations – go!”

But this is only the beginning. I want to make a feature – I want to make many features – and if I take this chance and squander it, well that’s the best way to shoot oneself in the foot. So I’m taking it seriously, and I’m very excited! It’s been marvellous. We had the opportunity to explore Durban, which is where we’ll be shooting, and get to know the foreign directors and other South Africans on the programme. I already feel a strong connection with some of the people.

GFM:

What’s next for you?

Zamo:

I have a wide variety of interests. Of course I’m South African, but I’m a little frustrated with the kinds of historical films that we’ve had in South Africa so far – they are all of a similar tone and cover the same subjects. For me that is a huge disservice to the people of South Africa, the ordinary people who really suffered the brunt of the past and, in many ways, still the present. At the moment I’m developing a historical film that’s about ordinary South Africans and certain events that for me make up the history of this country. It’s not the big events, it’s the small ones, and those are the stories that I feel strongly about.

I know that people say South Africans are stuck in the past and we need to get over it, but there are so many untold stories. To say we’re stuck in the past is to say those stories don’t matter, and that is a lie. It perpetuates a lie that I think many people have an interest in perpetuating – that the past never happened and that people are not still suffering from the consequences of that past. If we think about the Grand Prix winner at Cannes this year, it was the holocaust film Son of Saul, and it’s an incredibly important film. So I don’t see how, when this so-called Democracy in South Africa is only 21 years old, we can suddenly be saying “it’s all in the past” – no it’s not!

I am also interested in telling international stories. The Palme d’Or winner, Dheepan, was made by a French director telling a Sri Lankan story in Tamil. So I don’t think we should limit ourselves by telling stories that are only South African. There’s also this kind of feeling, which is that the first world is allowed to make stories about the third world, but we’re not allowed to turn the mirror around, which is incredibly patronising. I’m very interested in telling the mirror of that story.

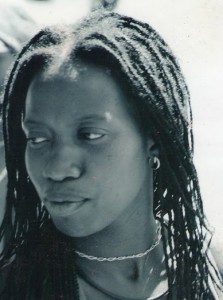

Director Zamo Mkhwanazi