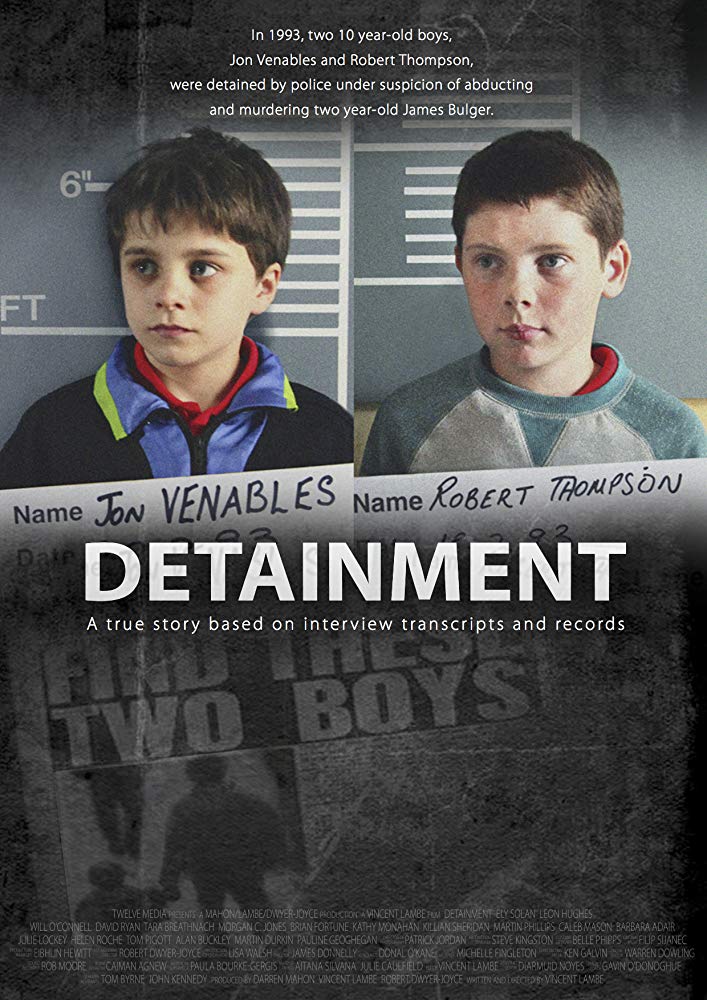

Directed by Vincent Lambe –

In 1993, ten-year-old friends Jon and Robert are brought to an English police station for questioning after CCTV footage implicates them in the kidnapping and murder of a two-year-old boy.

GFM: As I understand it, you’ve studied the James Bulger murder case for years and found that the police transcripts of interviews with the two ten year old murderers gave a much more nuanced picture of these boys, which differed from public opinion that generally accepted them to simply be evil. Can you comment on this and what led to your turning this into a film?

Vincent: Yeah, sure. I grew up hearing about this case. In the UK you can’t really not be aware of it, but most people I meet in America haven’t heard of it. In the UK, everybody still remembers it and you just say the name, James Bulger, and people feel the shudder they felt at the time. They think of those two boys and the malice that they had. The popular opinion at the moment is still that those two boys were simply evil. That’s why they did it. Anyone who suggests an alternative reason or tries to understand them is criticized and attacked for it. That’s happened to me as well. I understand why people feel that way and because when it happened people just couldn’t cope with the idea that these were ten year old boys. The only way they could make sense of it was if they were evil.

People have heard the same thing in the media for 26 years that these are evil monsters and the spawn of Satan because those are the headlines they’ve received. I think people have this image so ingrained in their heads that when they see them in the film as two ten year old boys, something doesn’t really sit right with them, and that’s when people think it’s being too sympathetic because they are shown not as the evil monsters of popular imagination, but as two young boys who something absolutely horrific. I understand that it’s a difficult thing for people to accept, but the film was never meant to be sympathetic to the boys. It’s not meant to make excuses for them, but it shows an authentic recreation of the interviews.

GFM: So you mentioned being criticized for putting this out there and there’s been a lot of pressure on you from James Bulger’s mother and others to withdraw the film from the Oscar competition. What I’d like to hear from you is what it’s like to be a filmmaker who’s now in the position of defending your art?

Vincent: I was always expecting there to be a certain amount of backlash with this case because I know how enormously sensitive it is. However, I was never expecting people to just report things about the film which are completely untrue. There’s been a lot of misinformation about the film in the UK. People are outraged by it because they’re believing it. They think there’s graphic violence in the film but there isn’t any violence whatsoever. A lot of people read something, which isn’t true or just very misleading. That causes them to get outraged by it. They think it’s a very different film. I hope people will see it and be able to watch it with an open mind. It’s just become available on iTunes.

GFM: Yeah, it’s packaged by Short’s TV, I believe, and it’s also being screened in theaters around the country in the US.

Vincent: That’s right. I think it’s also being screened in over 600 theaters around the world.

GFM: Your two young lead actors, Ely Solan, who plays Jon, and Leon Hughes, who plays Robert, turned in phenomenal performances. How did you cast them in their roles and direct their outstanding emotional performances?

Vincent: It was probably one of the biggest challenges to find these two incredibly talented child actors. They are great. I worked in casting for a long time and I worked as an agent for child actors. When I wasn’t directing, I was still directing by just holding thousands of auditions over 12 years. Without really knowing it, it taught me how to work with actors and effective ways to direct child actors. With the two boys we did the casting a little bit differently. I get them all to prepare a scene, as well as improvise at the end of the scene that they had prepared. I had an actor in the room reading with all the boys that we brought in. In the film, the detectives are quite gentle with their questioning but for the purpose of the casting, I had told them to just lose their rag with the boys and scare them a little bit. It almost took me by surprise but suddenly they weren’t acting anymore. It was great. It let us see what they were really capable of by themselves. All of them responded differently. It was interesting to see what they would do with it. Ely was incredible with the improvisation. He’s an extraordinary boy who’s just very in touch with his emotions and extremely bright and listens. He gives this emotionally raw performance as Jon in the film. Leon’s role as Robert was also very challenging . They’re probably two of the most demanding roles I’ve ever come across for child actors.

GFM: Tremendous! I also wanted to ask you about your history of making short films, which dates back to the late ‘90s and includes your award-winning film, Broken Things. Can you talk about your commitment to the short film format and its place in your career?

Vincent: There was a bit of a gap in making short films because I went into producing for a long time, but I always wanted to get back to making films. I think the more you produce, the more people see you as a producer. It took a long time for me to come back to it. With short films, I think it can do something that a feature can’t. Short films are more concise. You can get a message across in a very powerful way if it’s done right. You don’t need all of this padding or a slow build-up. You can get right in there. That’s why it was interesting working with that structure for Detainment when I was adapting the interview transcripts. We said that there’s a much wider story there. It only focuses on the interviews and it’s a small glimpse of them. But there’s a much broader story and it’s a heartbreaking one.

Short films can do some things well, but not everything. It just wasn’t possible to put the unimaginable pain of James Bulger’s family into the space of a short film. I don’t think you could do justice to it and I don’t think it would have been appropriate for us to try to do that. Really, Detainment looks at one small aspect of the case, which is the interviews.

GFM: Please could you tell our readers a little bit about Broken Things?

Vincent: Broken Things was my graduate film at film school back in 2002 and it’s probably a little bit dated. Filmmaking has changed a lot since then, and it’s a different film to Detainment. The one thing it probably does have in common is that it has a really excellent child performance by Diarmuid Noyes, who is still a good friend of mine. The story is about a boy who tries to escape his parents’ disintegrating marriage through his love for the piano.

GFM: My last question is what does the film’s Oscar nomination mean to you and for it to be widely seen and understood?

Vincent: It’s great to get the recognition from the Academy. I think the reason it’s been nominated is because they’re seeing it as a balanced and responsibly made film, which is why the misinformation didn’t bother me. I knew the Academy voters would still see the truth in it. I just hope people will be able to view it with an open mind. It’s great to get the recognition but at the end of the day I think it’s important for UK audiences to see the film.

Vincent Lambe