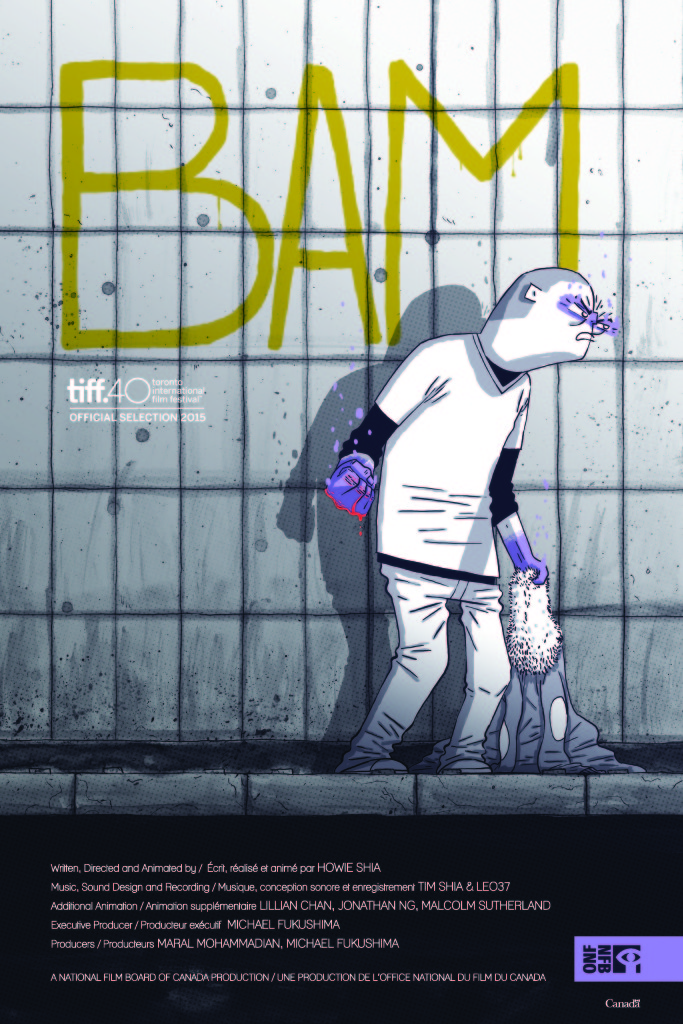

Directed by Howie Shia –

A young boxer struggles to contain the rage roiling inside him. Rendered in a spare but powerful style, this animated study in anger shifts from outbursts of brutal force to moments of quieter poignancy.

GFM:

BAM deals with a character who’s filled with rage and violence. How did you come to develop this type of story?

Howie:

There’s sort of two answers to that. I was living in Brooklyn at the time the idea came to me. I’d always been interested in boxing and wanted to make a film about it. My brother, who was one of the composers on the film, had always wanted to take that old animation trope of having drum solos behind boxing and fight scenes and try to do something that was actually not comical, to see if there was a way to make that emotionally resonant.

Once the story started to evolve, it became apparent that the violence involved in boxing is one of those rare things in our society that we sort of approve of, and it feels like it’s a functional use of that kind of energy. However, when you see violence on the news and online, there’s just all this rage. Salman Rushdie calls it ‘the outrage industry’. It seems like a kind of directionless anger, just anger for the sake of anger. So, part of it was just trying to understand the function of all of this rage. Clearly, we all have it in us, but where does it come from and what do we do with it? Is it an instinct or learned behaviour? In the film, we try to take it one step further and question if there’s some other sort of primordial divine right to this rage.

The other part of it is that my grandfather was an extremely classical Chinese man who on the one hand was a poet and calligrapher and loved tea and opera, and on the other hand was the chief of police and later one of three chief inspectors of the whole of Taiwan. He was an incredibly formidable man. When I tell people about him, the reaction is always one of surprise at the strange combination of traits. I think that it’s a fairly modern judgment because in my grandfather’s day, and when you look at heroes as they’re classically defined in literature and storytelling, they’re always on the one hand intellects and witty and artistic and sensitive but they also have this great capacity for righteous violence. So I think the question was to sort of transplant my grandfather into a modern context and see what kind of person he would be and what kind of decisions he would have to make. What do you do with all that power and anger and energy if you don’t have wars to fight and if you don’t have dragons to slay?

GFM:

Can you discuss your use of Greek mythology in the film, which contributes to its epic scope?

Howie:

Greek mythology is something that I generally always reference in my work, but in this case it was the question of dualities that I was interested in. I use a lot of imagery from Hercules, partly because he’s this dual person, half human and half god, as well as being a classically revered hero. In a lesser known story, however, he murdered his wife and children due to a divinely induced rage. So there’s this sense, I think, in mythology, where a lot of dichotomies and the partisan politics that we play nowadays don’t exist. Athena, for instance, is both the Goddess of the Hunt and the Goddess of Art and Poetry and nobody ever really questions that.

I wanted to have these characters in the film that were clearly resistant to the modern judgments, the modern dichotomies that we seem to adopt without question and to give the character this context of belonging in this classical world but sort of struggling through a modern reality.

GFM:

Your two brothers are musicians who you collaborate with regularly. How did that work on this project?

Howie:

We’ve always worked together, so it’s hard to differentiate between wrestling and working together. We all play instruments and are involved in music and art, so whenever we can we hop on each other’s projects.

In terms of working on this one, the brief from the NFB and Michael Fukushima was that he really wanted to see music play an important role in the film, so the animatic from the beginning to the finished film didn’t change that much, whereas I left very deliberate music-sized holes in the characters in some of the scenes and pacing so we could discover new things through the music.

There were several very different passes with the music but we ended up with kind of a mini opera, combining a lot of things we were listening to at the time – everything from George Benjamin and Donny MacCaslin to Benny Hill and Ennio Morricone, as well as the new D’Angelo and Kendrick Lamar albums.

GFM:

Tell us more about collaborating with the NFB.

Howie:

I just feel very fortunate to be with them. I sort of stumbled onto this opportunity from an open call for inexperienced animators to make very short films. I had a really good experience and was fortunate enough that everyone was very encouraging and I was able to do more films with them. The more we work together, the more privileged I feel to be part of the heritage of the NFB, especially when I travel abroad and talk to other animators and especially short filmmakers. The idea of an institution that has a mandate specifically to create short experimental animation that aggressively challenges the form and the emotional range of the audience and the artist is a wonderful thing to have for animation, but also in film and art in general.